“Across languages, speakers might hear a sound, but map it onto a different sound category in their own language, especially in contexts of background noise,” Sumner says. The British Royal Air Force adopted the same alphabet two years later.Īccording to NATO’s history of the phonetic alphabet, these earlier versions were criticized for their English bias because people from non-English speaking countries may be unfamiliar with the words used in those phonetic alphabets, potentially adding to the confusion when trying to communicate.

#Universal spelling alphabet code

Army and Navy established the “Able Baker alphabet,” named after the first two code words. This version primarily used names of cities and countries across the globe: Amsterdam, Baltimore, Casablanca, Denmark, and so on.

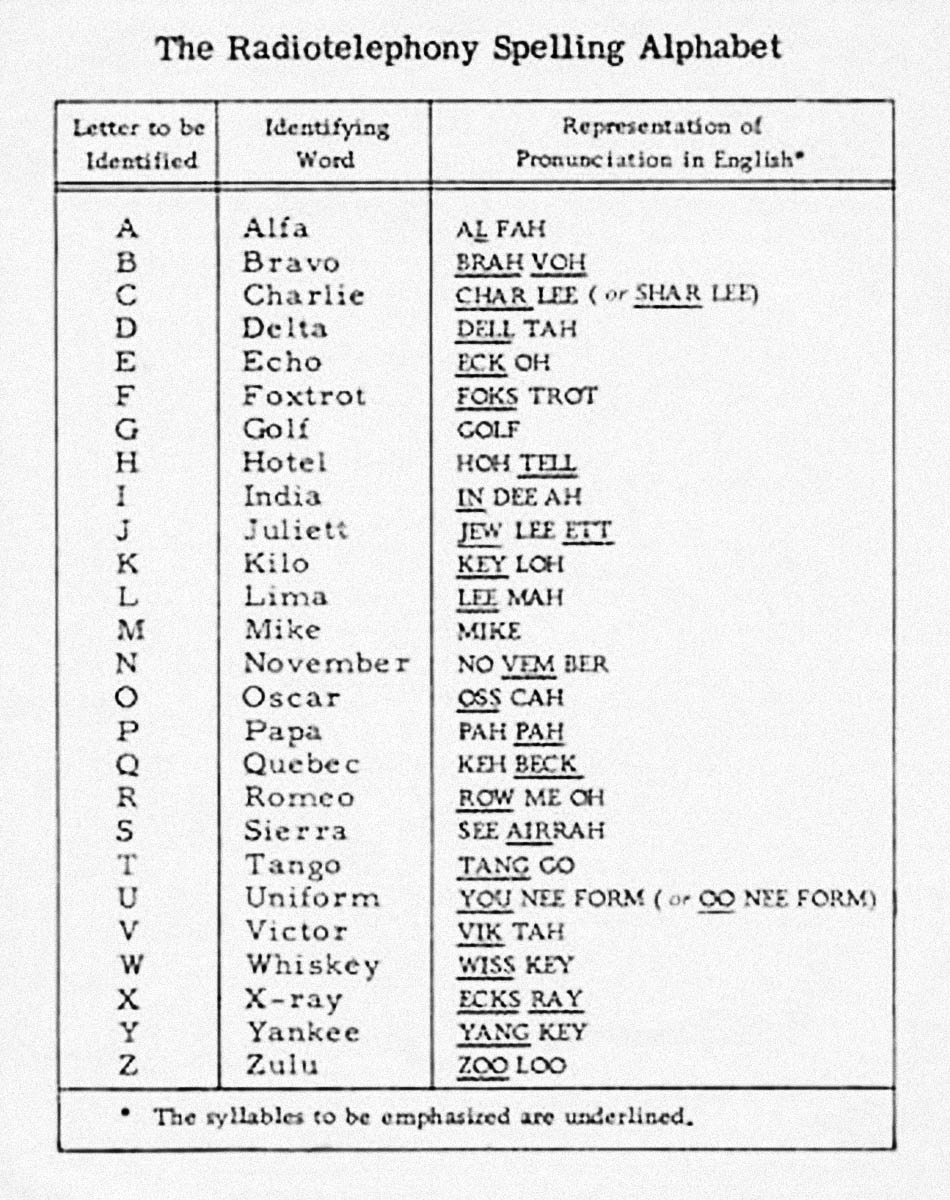

In the 1920s, a special agency of the United Nations, called the International Telecommunication Union (ITU), produced the first official version of a phonetic alphabet. However, several other variations preceded it. In the mid-1950s, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) became the first group to approve and use the new alphabet, hence its name.

The NATO phonetic alphabet helps avoid ambiguity and makes it clear what the letters are, she says. “Especially in contexts that are noisy or when you can’t see the talker, ” such as over a radio with background noise or interference. For example, the sounds “ th” and “ f” are very similar (thin, fin) and easy to confuse, as are “ m” and “ n” sounds, she explains. “Many sounds are highly confusable within a language,” Sumner says.

Usually, that kind of communication snafu is a minor inconvenience. The confused cashier tells you, “Hmm, I don’t have an order for ‘Kim.’ Someone just picked up an order for ‘Jim,’ and I have one here for ‘Tim.’” Standing in front of the cashier in the take-out line, you tell them your name so you can pick up that pizza you called in 20 minutes ago.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)